This realization then shined a light on the question asked by many internal gongfu practitioners, “Why does it take so long to get it?” To this, the typical response is, “If getting it were that easy, then everyone would be a master.” Well, we need a better answer than that! This series of posts is an attempt to provide a more thoughtful response to this question.

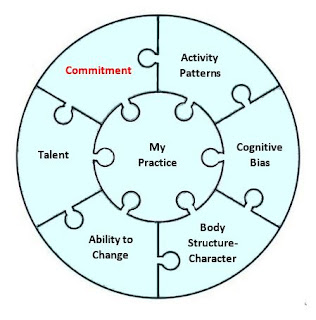

In the previous article in this series, I explored talent. In this post, I explore how Commitment and other closely related topics help or hinder my training.

For this component I debated whether to focus on Commitment or Motivation since the two are so intimately entwined; motivation inspires commitment, the results of which can further inspire motivation. As I pondered on this, I turned to the research on these topics and discovered there are actually different kinds of commitment and motivation.

As I read and interpreted these articles through the experience of my internal gongfu practice, I knew I had to present both. So first, I’ll present the topic and my description, so you’ll know why I found this topic relevant, and then I’ll present how these are applicable in the context of an internal gongfu practice.

COMMITMENT

I discovered that there are (at least) two ways to look at commitment: rational commitment and emotional commitment.

Rational Commitment

Rational commitment is a cognitive decision. I intentionally decide to commit time to deliberate practice (training). I intentionally use my cognitive tools to monitor and regulate my practice. Here I include Deliberate Practice and Time Commitment as elements of a rational commitment.

Deliberate Practice

Deliberate practice involves formalized exercises intended to improve skill. It is here that we find the various exercises, methods, and qigongs that are used in whatever art form you practice. These exercises have been rationally and intentionally designed to help you improve your skill. Sometimes these exercises can be boring, painful, frustrating, effortful, tedious and in a word, not for the faint-hearted. But they are exactly what is required to achieve the level of performance you are aiming to achieve.

Time Commitment

The exercises of Deliberate Practice must be practiced, often repeatedly, for a certain amount of time each day. Let’s revisit a model I used in Activity Patterns to get a sense of the percentage of time each day that I devote to practice.

Begin by looking at a typical 24-hour day. To facilitate calculations, disregard the eight-hour block of time devoted to sleep and only consider the remaining sixteen hours of waking experience.

(According to research, four hours is about the maximum time that even seasoned experts can sustain a focused, deliberate practice on a daily basis.)

Hours training per day Hours other Percentage of time committed to formal, deliberate practice (training) 1 hour 15 hours 6% of my day is committed to training 2 hours 14 hours 12.5% of my day is committed to training 3 hours 13 hours 18.5% of my day is committed to training 4 hours 12 hours 25% of my day is committed to training

Emotional Commitment

Emotional commitment occurs when the goals of practice support or enhance my goals in life, my self-image, and how I feel about myself. The amount of emotional commitment I direct toward practice is determined by the degree to which the goals of practice support or enhance my goals in life, my self-image, and how I feel about myself.

Unlike time commitment, emotional commitment is more difficult to quantify. Given that, I might suggest the following:

- 100% Emotional Commitment might look like an entire lifestyle built around practice.

- 50% Emotional Commitment might look like a hobbyist or a devoted enthusiast.

MOTIVATION

I discovered that there are several theories of motivation. The two that I mention here are the ones that resonate the most with my experience.

Intrinsic Motivation

A practitioner who is intrinsically motivated derives a sense of enjoyment from practice. The practice itself is personally important and highly valued.

Extrinsic Motivation

A practitioner who is extrinsically motivated engages in practice for the purpose of obtaining a reward or satisfying a demand. The reward or demand is more valued than the practice itself.

SELF-REGULATION

If rational commitment pertains to what I do, and emotional commitment and motivation pertains to why I do it, then self-regulation pertains to how I do it.

Self-regulation refers to the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral processes that the practitioner devises and strategically uses to monitor the effectiveness of the learning process. These processes include both internal and external feedback loops. Self-regulation shares nuanced similarities with self-control, self-management, self-directed behavior, and self-discipline.

_______

Application to Internal Gongfu

Now let me share how and why all this resonated with my learning experience.

When I was a kid, I marveled at the abilities portrayed on the TV show Kung Fu. When I got to college, I was single with no other commitments than school. College coursework and Tai-chi class together supported my image of myself. I had an intrinsic motivation. I practiced my forms two to three hours a day. I had both a rational and an emotional commitment. My self-regulation consisted of comparing my perception of my instructor’s form to my perception of my own form.

By the time I got to practicing Wujifa zhan zhuang, my entire life situation - priorities and values - had changed. I was married. I had a nine-to-five desk job, a mortgage, and a nearly full-time second job. Even though I could rationalize how stance practice would help me develop the abilities that I did not (and had longed to) develop in my previous practice, the most time commitment I could make was one hour a day. Zhan zhuang was so immeasurably different from any learning situation I had previously experienced, I did not know how to self-regulate and consequently I made many blunders along the way. My previous intrinsic motivation had waned and I was left with an extrinsic motivation – I practiced not for the enjoyment of it but for the want of the reward.

In Closing

To achieve expert-performance requires making a huge commitment of time and physical and emotional energy. Due to the unique nature of the practice, it may be that new self-regulation strategies will need to be developed. There may be a period of trial and error to figure out what is functional and what is not.

In hindsight, my earlier Tai-chi practice may have approached an overall 80% commitment but my Wujifa practice was probably more like an overall 20% commitment. If I were committed to my Wujifa training in the same way as I was committed to my earlier Tai-chi training, this would have helped my progress. However, with a diminished commitment and motivation, this no doubt hindered my progress.

Maybe the best time to make a commitment to practice is either as a child or young adult unencumbered by commitments of adulthood, career, and family. Maybe the next best time to make a commitment to practice is in retirement, unencumbered by commitments of career and family. Maybe the worse time to make a commitment to practice is during those years of career and family building like I tried to do.

With this puzzle now complete, this series will continue with considering how this puzzle can be interpreted in an Internal Gongfu Progress Matrix and finally we’ll look at the role of the Source and Level of Instruction.

References, Additional Reading

The role of emotions, motivation, and learning behavior in underachievement and results of an intervention. Stefanie Obergriesser* and Heidrun Stoeger. High Ability Studies. 2015, Vol. 26, No. 1, pp 167–190.

Relationships among cognition, emotion, and motivation: implications for intervention and neuroplasticity in psychopathology. Laura D. Crocker, et. al., Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. June 2013, Volume 7, Article 261, pp 1-19.

Evolving Concepts of Emotion and Motivation. Kent C. Berridge. Frontiers in Psychology. September 2018, Volume 9, Article 1647, pp 1-20.

Coach-Created Motivational Climate and Athletes’ Adaptation to Psychological Stress: Temporal Motivation-Emotion Interplay. Montse C. Ruiz, et. al. Frontiers in Psychology. March 2019, Volume 10, Article 617, pp 1-11.

When quantity is not enough: Disentangling the roles of practice time, self-regulation and deliberate practice in musical achievement. Arielle Bonneville-Roussy and Thérèse Bouffard. Psychology of Music. Vol. 43(5), 2015, pp 686–704.

Using Wise Interventions to Motivate Deliberate Practice. Lauren Eskreis-Winkler, et. al. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Vol. 111, No. 5, 2016, pp 728–744.

Creativity and talent. Chapter 28. (pp. 371–380). Winner, Ellen. In Well-being: Positive development across the life course. M. H. Bornstein, L. Davidson, C. L. Keyes, & K. A. Moore (Eds.). Mahwah, N.J. : Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2003.

Comparing students’ self-discipline and self-regulation measures and their prediction of academic achievement. Barry J. Zimmerman, Anastasia Kitsantas. Contemporary Educational Psychology. Vol 39, Iss 2, 2014. pp 145–155.

Previous post in this series: Mastering Internal Gongfu: Are You Ready? Talent

Next post in this series: Mastering Internal Gongfu: Are You Ready? The Progress Matrix